By Kathleen Oswalt-Forsythe

Nostalgia and I are long-time friends. Growing up the fourth generation on a family farm, I eagerly welcomed this constant companion. Reminders of the previous generations and their hard work were visible daily: the hay barn’s hand-hewn beams, the old horse collar in the shop, the field stone foundations. My great-grandparents planted two pear trees to the west of the farmhouse in 1908. From my bedroom window, I could watch those knobby branches drop their fall fruit, twiggy fingers wiggling in the breeze.

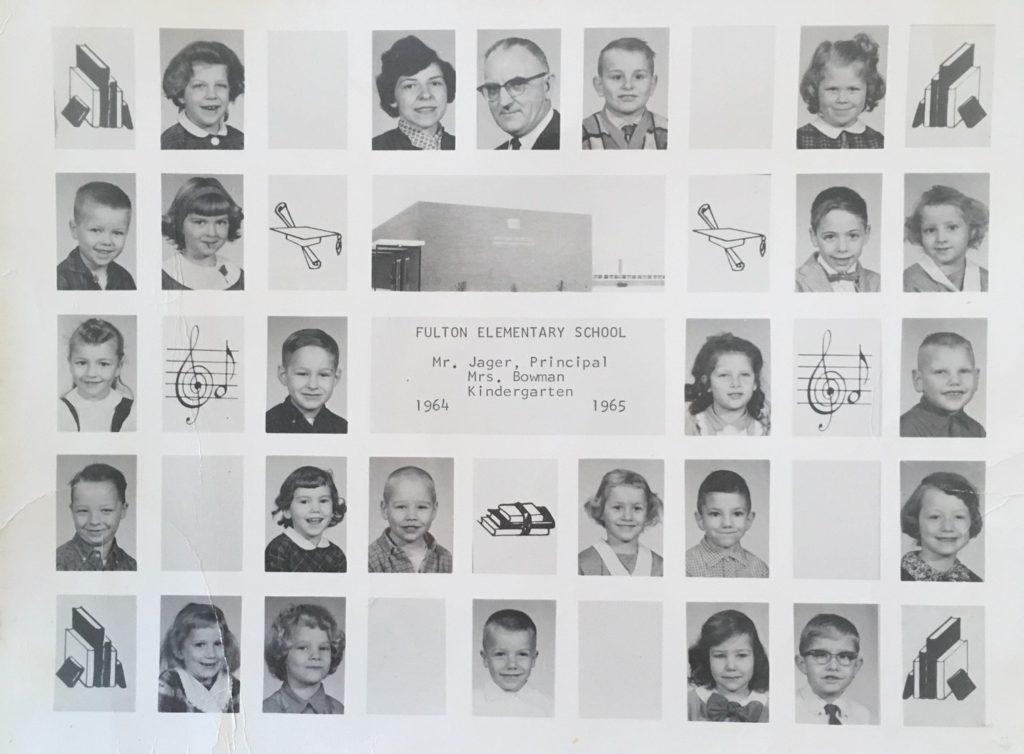

The childhood faces of my father, uncle, and their neighbors smile from their annual school picture on the steps of the Harper School – a charming old black-and-white photo in my album. Dad’s one-room-schoolhouse days were part of our growing-up-folklore: the mile walk to school, the tag and softball games at recess; the neighborhood’s contribution to salary and firewood. It all sounded magical to me.

When I started kindergarten, I rode to Fulton Elementary School with my grandmother – our 4th grade teacher – in her white Thunderbird. I couldn’t see over the dashboard, so I watched the trees click by or traced the powerlines as we drove the six miles to school. I loved being with her – my striking grandmother in her little tweed suits with the lapel pins, her suntan hose, and her spectator pumps. After parking, she opened the car’s heavy door for me, saying, “Have a good day, dolly.” I assumed everyone’s school experience was as wonderful as mine; the only way it could possibly be better would be going to “country school.”

Last spring, a frank discussion with my mother-in-law about her one-room-schoolhouse experience revealed a different narrative. She had attended several one-room-schools in rural Illinois before going to high school in a larger town. My mother-in-law is smart, loves numbers, and remembers everything. I’m sure she was a sharp and thorough student, quickly finishing anything her teacher assigned. But when she finished one year and entered a different “country school,” she learned that her teacher had not introduced her to important math concepts, leaving her terribly unprepared for the next year’s expectations. “I was angry. I had lots of work to do to catch up.” Catch up she certainly did, but it was disappointing and stressful for her.

So those really weren’t the “good old days” for many students. Isolation and lack of support in outlying areas created gaps in student learning I hadn’t considered. Today, teachers plan and team at grade level, following curriculum that guarantees students’ exposure to the most important standards. Also, in the 1940s and ‘50s, many students didn’t go beyond the 8th grade. Many students today are eligible for and receive much needed services and supports, also helping more students complete their schooling.

I will always enjoy looking at those charming school photos or seeing the old structures on Sunday drives, but I am also reminded of the historical and continued need for equity and opportunity for all students.

It’s a Fine Life

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

My dad and I enjoyed this story. The main character is a teacher in the rural west.

In fourth grade, my grandmother read these books to our class as we rested our heads on our cool desks after recess. I just loved them and imagined being Laura.

If you haven’t read this book, do. It is amazing.