By Kathy Oswalt-Forsythe

Until recently, the wagon wheel leaned in the hay loft of the old cattle barn, where for the last forty years it had been collecting dust and cobwebs, nearly forgotten. Its spokes were intact, the outer hoop, nicked and scarred but still holding strong, a testimony to the history of our family’s centennial farm operation in Southwest Michigan’s Kalamazoo County.

Our great-grandparents purchased the original ground in the late 1800s; they built the house, barns, and outbuildings soon after. They began clearing and tiling the rich loamy soil of the low ground, eventually used to grow mint and grains, and created pastures and fields in the higher ground.

Our great-grandparents fed a variety of animals, including sheep, hogs, and cattle, and they had a small dairy, as did many farms in our area. They gradually added to the operation and acquired more ground to produce more feed for the animals, as well as grain to market.

Our grandparents eventually took over this farm, where growing grains and purchasing and feeding calves became its focus, and Dad and Uncle John naturally continued the business.

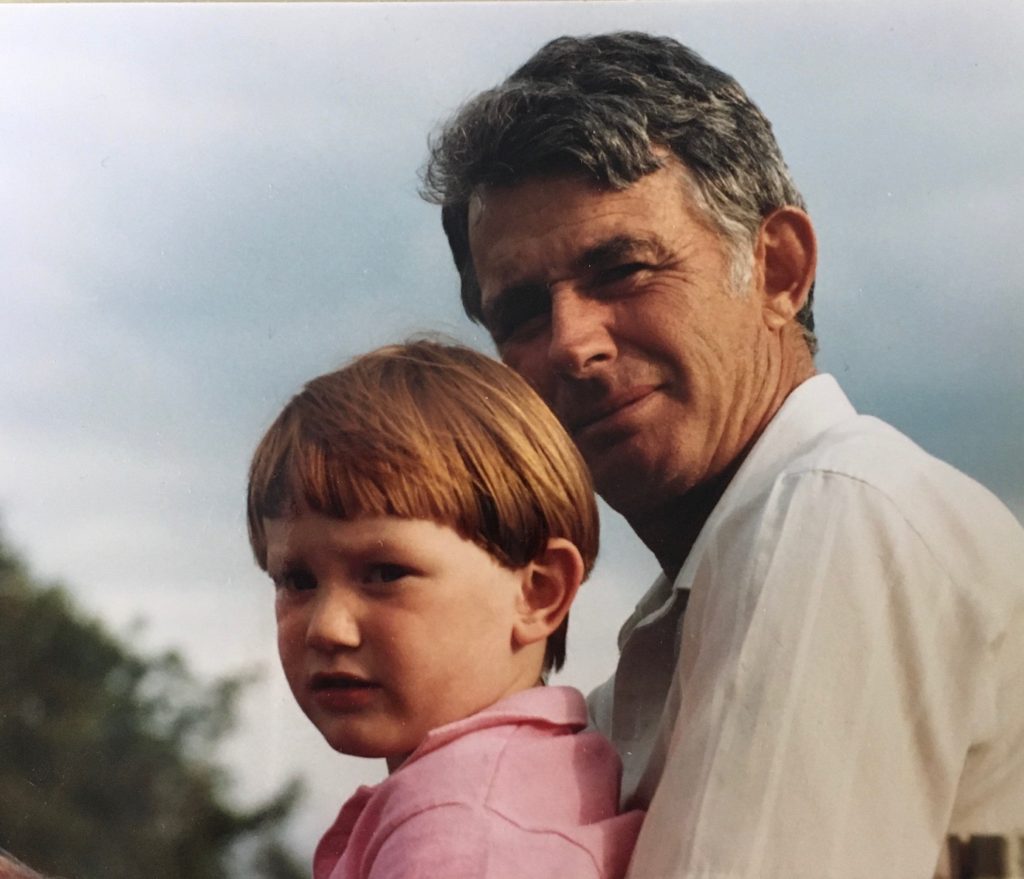

My four brothers, our cousins, and I, the 4th generation, grew up on the farm. My brothers and I lived in the farmhouse. All of us also learned to work hard and to care for and love the farm.

Several of my earliest memories are with my dad as he worked–sitting on his lap, his chin resting on my tiny head, as he cultivated corn. I was content, mesmerized by Dad’s humming and the green lines of the young corn plants as we traveled back and forth through the field. I’m sure my brothers have the same memory.

Or Mom packing up our lunch or supper, taking us to whatever field Dad was working. We sat in the shade along a fencerow, hearing about Dad’s day and sharing events from ours.

Or helping Dad with chores, feeding calves in the barn in the evening, directly across the street from our home, using a cart which at that time was supported by the long-abandoned wheel.

The feed cart fit perfectly in the aisle that led between two concrete feed bunks that spanned the length of the barn. When I was little, Dad fed cattle the same way his father and grandfather had fed them. He loaded sileage from the silo, frequently by hand as our silo-unloading-machine was often broken. He climbed that eighty-foot concrete-block silo rung by rung, carrying an aluminum shovel. He eventually stepped from the ladder to the sileage, then shoveled the feed down the shoot, into the cart, waiting below.

I stood in the alleyway, listening to the feed hit the cart, shovelful after shovelful.

Then he climbed backdown the shoot and pulled the cart to the far end of the feed alley.

With the strength of Dad’s shoveling, the cart was pushed farther and farther down the alley. When the cart was empty, Dad would start the loading process again. It took probably two or three climbs of the silo for those evening feeds.

Eventually, the operation changed, and the silo stood empty. Dad stacked the sileage outside in a huge open-air concrete bunker, and he loaded chuck wagons using a tractor or front loader. Some animals were fed in an outside feed bunk, and some animals were fed on pasture.

The old wooden feed cart was rolled to the corner of the hay loft where it slept silently, like Rip Vanwinkle, for 40 years.

Two of my four brothers eventually joined the farm operation full-time, which enabled the business to expand the existing angus cow calf herd and commercial sheep flock.

In 2014, our parents restored the old cattle barn—a point of pride for Mom and Dad–and about that time, the old wheel was moved to the front of the farm office where it sat until a year ago.

Two of my nieces now work part-time on the farm where they encouraged my brothers to open a farm retail store within the existing farm office, and during the last year that space was created.

The wheel now has a new life—providing the structure for a light that shines brightly in the retail store.

It is a symbol of the circle of time, of generations past and their hard work.

It represents the life of a family and its farm ground and animals, carefully tended throughout five generations. And, as in the past, now the sixth generation is learning to love and care for the land and the animals.

It’s a Fine Life