I contracted pony fever in fourth grade. It simmered and rose throughout the weeks, kindled by my dad’s stories of his boyhood. He and my Uncle John grew up on our farm with gentle draft horses and a beloved pony named Major, a favorite character in Dad’s tales of their childhood adventures.

My infection reached a critical level one evening when our new neighbors, the Wickies, rode the mile to our farm on horseback for a visit. Each of the four kids (ages five to fourteen) had a pony. And while they weren’t wearing fringed western gear like Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, and they didn’t talk like the cowboys in the movies, those kids sure seemed like they knew what they were doing.

After a short conversation—and several pony parades—the Wickies smiled down at my brothers and me, waved, and turned their obedient steeds towards home.

They were living the best life I could imagine.

My quest for a horse-fever-cure began then in earnest.

I read my mom’s childhood novels by Marguerite Henry, checked numerous books out of our school library, and certainly dropped countless hints and suggestions about horses.

My life just wasn’t complete. I needed a pony.

One Sunday in early spring we headed home from church. Dad had chores to do that day and had stayed home. As we pulled into our driveway, Mom said, “Kids, look at your dad!”

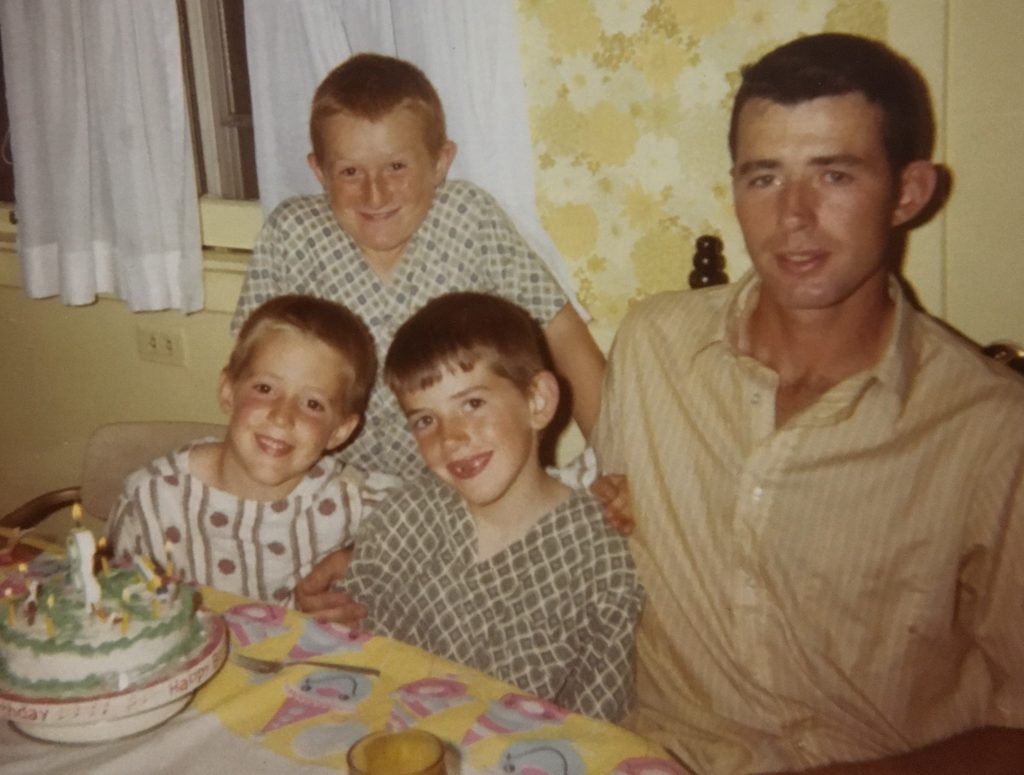

I peered over the station wagon’s backseat and there, in the driveway, was my dad, leading a beautiful brown pony.

We tumbled from the car and ran towards Dad.

“Woah, woah, woah.,” Dad directed. “You need to come slowly. And DON’T stand behind him.”

We crept quietly forward and stood beside Dad.

“Is he ours?” I asked.

“Yup, his name’s Buttons,” my dad replied.

I stroked Buttons’ brown face and touched his whiskered, gray-velvet nose as he swished his tail and stomped his feet.

“Okay, come on, let’s go,” Dad said.

My dad was always casual and brief in delivering instruction; he subscribed to the theory that it was best for children to just “figure things out.” He quickly showed us how to put on the blanket and cinch the saddle. This was after he removed the saddle’s stirrups explaining he didn’t want us to “have our feet caught” if we fell off the pony.

Then Dad helped me into the saddle, led us into the back yard, and set us loose.

Now, even though I had read everything I could find about horses, I had never really been on a horse.

I had ridden the ponies that circled endlessly at the county fair.

When I was four, I sat in front of my dad on his horse, Monty Boy, as he slowly walked around the pasture.

But Monty Boy had been gone since I was five, and carnival pony rides don’t really prepare a girl for independent riding.

So, without stirrups and previous practice, I bounced off Buttons every time he moved to a trot. After every fall, I scrambled to my feet and my brothers and I cornered and grabbed Buttons’ reins. Dad was nowhere in sight–busy with his work and unavailable. He must have assumed we were happily and skillfully riding our new pony.

To add another insult, at day’s end, Buttons bit me as I gently removed his bridle, leaving a painful purple imprint of his teeth just above my knee.

I never did “figure out” and master riding—or overcome my fear of being bitten or thrown from my longed-for steed. It turned out that Buttons was gifted at brushing off his young riders and viciously biting whenever my dad wasn’t in his sight, which was most of the time.

I don’t think we kids complained or asked for help. I’m not sure Dad ever fully realized our difficulties.

I never succeeded in making Buttons behave. I confess, I am an equestrian flunky. My illness cured.

But I will never forget that day: the thrill of my dream fulfilled, the sight of that beautiful pony, and the happiness in my sweet dad’s smile.

It’s a Fine Life